Please set your exam date

Pediatric Nursing Skills and Pediatric Assessment

Study Questions

Introduction

Explanation

A. Correct. When assessing a pediatric patient, it is crucial to communicate in a way that is age-appropriate and tailored to the child's developmental level. This helps establish trust and cooperation during the assessment process.

B. Incorrect. Avoiding all physical contact may hinder the nurse's ability to perform a thorough assessment. Some physical contact may be necessary, but it should be done with sensitivity and respect for the child's comfort.

C. Incorrect. While involving parents in the assessment process is important, relying solely on their information may not provide a complete picture of the child's health.

D. Incorrect. While efficiency is important, rushing through the assessment can lead to missed information and potential errors.

Explanation

A. Correct. When a parent expresses concerns about a child's development, it is important to recommend seeking professional evaluation and assessment. This ensures that any potential issues are identified and addressed in a timely manner.

B. Incorrect. Waiting until the child starts school may delay necessary interventions if there are developmental concerns.

C. Incorrect. While online forums can be a source of information, they should not replace professional evaluation and advice.

D. Incorrect. Disregarding the concerns without further assessment may lead to missed opportunities for early intervention if there are developmental issues.

Explanation

A. Incorrect. Installing safety gates at the top and bottom of stairs is a recommended safety measure to prevent falls.

B. Incorrect. Keeping small objects out of a child's reach is essential to prevent choking hazards.

C. Correct. Using a soft mattress in the crib can increase the risk of suffocation or sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS). It is important to use a firm mattress to ensure the infant's safety.

D. Incorrect. Securing cabinet doors to prevent access to cleaning supplies is an important safety measure to protect the child from potential hazards.

A client is worried because their 9-month-old infant has not started walking yet. What should the nurse explain to the client?

Explanation

A. Correct. Walking usually begins between 12-15 months of age, but the range of normal development is broad. Some infants may start earlier or later and still fall within the normal range.

B. Incorrect. Expecting a 9-month-old infant to already be walking is not realistic. Walking typically starts later in the first year.

C. Incorrect. Not all infants follow the exact same developmental timeline. A delay in walking does not necessarily indicate a developmental issue.

D. Incorrect. Consulting a pediatric orthopedic specialist at this stage is premature and not indicated solely based on a delay in walking.

Explanation

A. Incorrect. While some infants may start experimenting with self-feeding, it is not a universal milestone at 6 months.

B. Incorrect. While weight gain is important, it is not a specific developmental milestone.

C. Correct. Around 6 months, infants typically begin to develop the ability to sit unsupported. This is an important milestone in their physical development.

D. Incorrect. Preference for solitary play is a social and emotional aspect of development, but it is not the primary milestone expected at 6 months.

Explanation

A. Correct. Establishing a consistent bedtime routine and sleep schedule helps regulate a toddler's sleep patterns and promotes healthy sleep habits.

B. Incorrect. Allowing a toddler to stay up late can disrupt their natural sleep-wake cycle and may lead to sleep difficulties.

C. Incorrect. Introducing herbal tea may not be suitable for young children and is not a recommended strategy for improving sleep patterns.

D. Incorrect. While avoiding excessive daytime naps can help regulate nighttime sleep, completely avoiding naps may lead to overtiredness, which can also disrupt sleep.

Explanation

A. Correct. It is crucial to emphasize the importance of following the recommended vaccination schedule to provide the child with optimal protection against preventable diseases.

B. Incorrect. Delaying or skipping vaccines can leave the child vulnerable to serious illnesses. It is important to discuss any concerns with the healthcare provider rather than deviating from the recommended schedule.

C. Incorrect. Administering multiple vaccines at once is a common practice and is safe and effective. It helps protect children against diseases efficiently.

D. Incorrect. Waiting until the child starts school can leave them susceptible to diseases that could have been prevented through timely vaccinations.

Explanation

A. Correct. Large, colorful blocks promote gross motor skills, creativity, and problem-solving abilities in a 1-year-old child.

B. Incorrect. Small, intricate puzzles may pose a choking hazard for a 1-year-old and are not suitable for their developmental stage.

C. Incorrect. Toys with small parts can be a choking hazard and are not recommended for children of this age.

D. Incorrect. Complex board games are not developmentally appropriate for a 1-year-old and may be frustrating rather than beneficial.

Vital signs measurement

Explanation

A. Incorrect. Pulling the child's earlobe down and back is a technique used for straightening the ear canal in older children and adults, not for using a tympanic thermometer.

B. Correct. When using a tympanic thermometer, it's important to gently insert the probe into the ear canal and ensure a proper seal. This helps to obtain an accurate temperature reading.

C. Incorrect. Holding the thermometer in place for 1-2 minutes is not the correct technique for tympanic temperature measurement. It may lead to an inaccurate reading.

D. Incorrect. Using an oral thermometer for a 2-year-old child is not the recommended method, as it may not provide an accurate temperature reading.

Explanation

A. Incorrect. A cuff that covers only 50% of the upper arm circumference may be too small and lead to falsely elevated blood pressure readings.

B. Correct. Selecting a cuff that covers approximately 75% of the upper arm circumference is recommended for accurate blood pressure measurement in children. This ensures proper fit and accurate readings.

C. Incorrect. Using a cuff that covers 100% of the upper arm circumference may be too large, resulting in falsely low blood pressure readings.

D. Incorrect. A cuff that covers 125% of the upper arm circumference is overly large and not appropriate for accurate blood pressure measurement.

Explanation

A. Correct. Placing the hand on the infant's abdomen allows the nurse to feel the rise and fall with each breath, providing an accurate count of respiratory rate.

B. Incorrect. Counting respirations while the infant is sleeping may be challenging and may not provide an accurate assessment.

C. Incorrect. While visually observing chest movement can be helpful, this method may not be as accurate as feeling the actual movement with the hand.

D. Incorrect. Using a stethoscope to listen for breath sounds is not the recommended method for measuring respiratory rate in infants.

Explanation

A. Incorrect. Palpating the brachial artery is not the recommended method for measuring the apical pulse.

B. Correct. Measuring the apical pulse with a stethoscope over the apex of the heart allows for accurate assessment of the heart rate in infants.

C. Incorrect. Using the radial pulse is not the appropriate method for measuring the apical pulse in infants.

D. Incorrect. Counting the pulse at the carotid artery is not the recommended method for assessing the apical pulse in infants.

Explanation

A. Incorrect. Weighing the child while wearing clothes may lead to an inaccurate measurement. It's best to weigh the child without excess clothing.

B. Incorrect. Using a bathroom scale designed for adults is not suitable for accurately measuring a toddler's weight.

C. Correct. Using a flat, stable surface for weighing ensures accuracy in measurement.

D. Incorrect. Allowing the child to hold onto a toy during the measurement may introduce additional variables that could affect the accuracy of the weight measurement.

Explanation

A. Correct. Having the child stand against a wall and marking their height with a pen provides an accurate measurement of height in children who are able to stand.

B. Incorrect. Instructing the child to lie down on the examination table is not the appropriate method for measuring height in a standing child.

C. Incorrect. Using a tape measure to measure the distance from head to toe is not as accurate as having the child stand against a wall for measurement.

D. Incorrect. Estimating height based on age and weight is not a reliable method for obtaining an accurate measurement.

Explanation

A. Correct. Using the index and middle fingers to palpate the pulse provides a more accurate assessment of the radial pulse.

B. Incorrect. Using the thumb to apply pressure to the radial artery can inadvertently compress the artery, leading to an inaccurate pulse reading.

C. Incorrect. Applying strong pressure may interfere with the pulse assessment and is not necessary for detecting the pulse rhythm.

D. Incorrect. Counting the pulse for 10 seconds and multiplying by 6 is a valid method, but using the index and middle fingers for palpation is preferred for accuracy.

Explanation

A. Incorrect. Counting respirations immediately after eating may not provide an accurate measurement, as activity or digestion can influence respiratory rate.

B. Correct. Observing chest movement for a full minute allows for an accurate assessment of respiratory rate in children.

C. Incorrect. While using a stopwatch may be helpful, it is not necessary to ensure an accurate respiratory rate measurement in this context.

D. Incorrect. Asking the child to take deep breaths may not reflect their natural respiratory rate and could lead to an inaccurate assessment.

Physical examination

Explanation

A. Incorrect. Depressed and sunken fontanelles are signs of dehydration and should be evaluated promptly.

B. Incorrect. Flat and firm fontanelles may indicate normal hydration, but slight bulging is considered normal in infants.

C. Correct. Slightly bulging fontanelles can be normal in infants due to crying, coughing, or changes in intracranial pressure. However, severely bulging or depressed fontanelles are concerning and require further evaluation.

D. Incorrect. Pulsating fontanelles are a normal finding and are related to the pulsations of blood flow in the area.

Explanation

A. Correct. Using the Snellen eye chart is a standard method for assessing visual acuity in children who can cooperate with the test.

B. Incorrect. Asking the child to identify colors is not a specific test for visual acuity.

C. Incorrect. Using an ophthalmoscope is a tool for examining the internal structures of the eye, not for assessing visual acuity.

D. Incorrect. Observing eye movements is important for assessing coordination and alignment of the eyes but does not directly measure visual acuity.

Explanation

A. Incorrect. Assessing only axillary nodes would miss important areas for lymph node examination in a child.

B. Incorrect. Assessing only inguinal nodes would miss important areas for lymph node examination in a child.

C. Correct. When assessing lymph nodes in a child, it's important to include the cervical (neck), axillary (armpits), and inguinal (groin) nodes in the examination.

D. Incorrect. Popliteal nodes are not typically assessed in a routine pediatric examination.

Explanation

A. Correct. The Ortolani maneuver is used to assess for developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH) in infants. It involves gently abducting the hips while applying gentle pressure to feel for any instability.

B. Incorrect. The Barlow maneuver is also used to assess for DDH, but it involves adducting the hips.

C. Incorrect. The Phalen maneuver is used to assess for carpal tunnel syndrome, which is not relevant to hip stability.

D. Incorrect. Tinel's sign is used to assess for nerve compression, typically in the wrist, and is not relevant to hip stability.

Explanation

A. Incorrect. Genu varum (bowleggedness) is normal in infants, but it typically resolves as the child grows.

B. Incorrect. Kyphosis, an excessive forward curvature of the upper spine, may be normal to some degree, but it should not be excessive or cause discomfort.

C. Correct. Lordosis, or an inward curvature of the lumbar spine, is considered normal in children, particularly during early childhood. Genu varum (bowleggedness) is also normal in infants but typically resolves as they grow.

D. Incorrect. A perfectly straight spine alignment is not typically seen and may indicate an issue.

Explanation

A. Incorrect. Asking the child to recite the alphabet may assess their knowledge of letters, but it does not specifically evaluate articulation.

B. Incorrect. Observing the child's response to questions is important for assessing language comprehension, but it does not specifically target articulation.

C. Correct. Assessing articulation involves having the child repeat sounds, words, or sentences to evaluate their ability to form sounds and words correctly.

D. Incorrect. Using a tongue depressor to examine the mouth is not relevant to assessing articulation.

Explanation

A. Incorrect. The Babinski reflex, where the big toe extends and the other toes fan out, is normal in infants but typically disappears by the age of 2.

B. Correct. The Moro reflex is a normal startle response in newborns. It involves symmetrically spreading the arms and then bringing them back to the body when the infant experiences a sudden change in position or stimulation.

C. Incorrect. The tonic neck reflex, also known as the "fencing" reflex, is a normal infantile reflex but typically disappears by 6 months.

D. Incorrect. The plantar grasp reflex, where the toes curl in when the sole of the foot is touched, is normal in infants but typically disappears by 9 months.

Explanation

A. Incorrect. Sitting without support typically occurs around 6-8 months.

B. Incorrect. Walking with assistance usually begins around 9-12 months.

C. Correct. Rolling from back to front is an expected motor milestone for a 6-month-old infant. Other milestones, such as sitting without support and crawling, may occur at later stages of development.

D. Incorrect. Crawling on hands and knees typically occurs around 7-10 months.

Developmental Assessment

Explanation

A. Incorrect. Rolling from back to front is not typically achieved at 2 months.

B. Incorrect. Holding a rattle is a skill that usually develops around 4-6 months.

C. Correct. By 2 months, infants should be able to lift their head and chest when placed in a prone position. This indicates appropriate neck and upper body strength development.

D. Incorrect. While smiling responsively is a social milestone, it is usually present earlier, around 6-8 weeks.

A client brings their 6-month-old infant for a well-child visit. The nurse is assessing the infant's motor development. What milestone should the nurse expect the infant to have achieved at this age?

Explanation

A. Correct. By 6 months, infants should be able to sit without support, although they may still wobble or need to use their hands for balance.

B. Incorrect. Walking with assistance typically begins around 9-12 months.

C. Incorrect. Rolling from back to front is a skill that is usually mastered earlier, around 4-6 months.

D. Incorrect. Crawling on hands and knees typically occurs around 7-10 months.

Explanation

A. Incorrect. Using a fork and spoon independently is a fine motor skill, but it is typically mastered by the age of 4.

B. Correct. Drawing a circle is a developmentally appropriate fine motor skill for a 3-year-old child. It demonstrates the ability to control hand movements and coordination.

C. Incorrect. Counting to 20 is more advanced and typically achieved by children older than 3.

D. Incorrect. Riding a bicycle without training wheels is a gross motor skill that is usually acquired around 5-6 years of age.

Explanation

A. Incorrect. Reciting the alphabet primarily tests rote memory and may not accurately reflect a child's language development.

B. Incorrect. Observing the child's response to questions is important but does not specifically target language development.

C. Correct. Having the child name familiar objects assesses their expressive language skills and vocabulary.

D. Incorrect. Using a tongue depressor to examine the mouth is not relevant to assessing language skills.

Explanation

A. Correct. By 8 months, infants should have developed the ability to grasp objects using their thumb and forefinger in a pincer grasp.

B. Incorrect. Using a spoon independently is a skill that is typically developed later, around 12-18 months.

C. Incorrect. Walking with assistance is a gross motor skill that is usually achieved later, around 9-12 months.

D. Incorrect. Rolling from back to front is a skill that is typically mastered earlier, around 4-6 months.

Explanation

A. Incorrect. Engaging in parallel play (playing alongside other children without direct interaction) is more typical of toddlers around 2 years old.

B. Incorrect. Initiating complex games with peers may occur later, around 3-4 years old.

C. Correct. Around 15 months, toddlers typically begin to exhibit stranger anxiety, which is a normal developmental response to unfamiliar individuals.

D. Incorrect. Independent dressing is typically achieved later, around 2-3 years old.

Explanation

A. Incorrect. Understanding the concept of conservation of volume is a more advanced cognitive skill typically mastered later, around 7-8 years old.

B. Incorrect. Solving complex mathematical equations is beyond the cognitive abilities of most 6-year-olds.

C. Correct. Identifying primary colors is a developmentally appropriate cognitive skill for a 6-year-old child.

D. Incorrect. Recognizing abstract concepts is typically a more advanced cognitive skill and is not expected at this age.

Explanation

A. Correct. Reviewing recent report cards and standardized test scores provides valuable information about the child's academic performance and learning abilities.

B. Incorrect. Observing play activities is important for assessing social and emotional development but may not provide specific information about academic abilities.

C. Incorrect. While reciting times tables is a math skill, it does not provide a comprehensive assessment of overall learning abilities.

D. Incorrect. Performing a neurological examination is not typically indicated for assessing academic performance.

Psychosocial Assessment

Explanation

A. Correct. Engaging in parallel play (playing alongside other children without direct interaction) is typical for a 5-year-old child. Cooperative play (playing together with interaction) tends to develop more around 3-4 years of age.

B. Incorrect. Engaging in cooperative play is a more advanced social skill and may not be as common at this age.

C. Incorrect. Demonstrating stranger anxiety is more commonly seen in younger children, particularly toddlers.

D. Incorrect. Initiating complex games with peers is typically seen in older children.

Explanation

A. Incorrect. Engaging in parallel play (playing alongside other children without direct interaction) is more typical of toddlers around 2 years old.

B. Incorrect. Initiating complex games with peers may occur later, around 3-4 years old.

C. Correct. Around 15 months, toddlers typically begin to exhibit stranger anxiety, which is a normal developmental response to unfamiliar individuals.

D. Incorrect. Independent dressing is typically achieved later, around 2-3 years old.

Explanation

A. Correct. By the age of 10, children typically start to identify and form peer groups, indicating a developmentally appropriate desire for social interaction and belonging.

B. Incorrect. Engaging in solitary play is more characteristic of younger children and may not align with the social needs of a 10-year-old.

C. Incorrect. While some degree of egocentrism may still be present, it is more characteristic of younger children.

D. Incorrect. Demonstrating autonomy is important but is not specific to psychosocial development at this age.

Explanation

A. Correct. Asking about relationships with peers provides insight into the adolescent's social interactions and can be an important indicator of psychosocial well-being.

B. Incorrect. While academic achievements are important, they do not directly assess psychosocial health.

C. Incorrect. Observing gross motor skills is not relevant to assessing psychosocial health.

D. Incorrect. Assessing blood pressure and heart rate is important for physical health but does not address psychosocial concerns.

Explanation

A. Incorrect. Parallel play (playing alongside other children without direct interaction) is common in toddlers but is not specifically related to psychosocial development at this age.

B. Incorrect. Cooperative play (playing together with interaction) is more characteristic of older preschool-aged children.

C. Incorrect. Independence in dressing is a fine motor skill and is not directly related to psychosocial development.

D. Correct. Exhibiting stranger anxiety is a normal developmental response in young children, indicating a growing awareness of unfamiliar individuals.

Explanation

A. Incorrect. A strong attachment to a security object is more characteristic of younger children.

B. Correct. Around 8 years of age, children often exhibit a desire for increased independence and autonomy, reflecting a normal aspect of psychosocial development.

C. Incorrect. While some children may engage in competitive sports, it is not a universal indicator of psychosocial development at this age.

D. Incorrect. Adolescent-like mood swings are not typically seen in children of this age group.

Explanation

A. Correct. By 16 years of age, adolescents are typically capable of forming more intimate and meaningful relationships with peers, indicating a normal progression of psychosocial development.

B. Incorrect. While some degree of egocentrism may still be present, it tends to decrease in intensity as adolescents mature.

C. Incorrect. Parallel play is more characteristic of younger children and is not a typical behavior for adolescents.

D. Incorrect. Stranger anxiety is more commonly seen in younger children and may not be relevant to psychosocial development at 16 years of age.

Explanation

A. Correct. Asking about hobbies and interests provides an opportunity to explore the preadolescent's social interactions, preferences, and potential areas of social development.

B. Incorrect. Reviewing growth chart and physical development may be important for overall health assessment but does not specifically address social interactions.

C. Incorrect. Assessing fine motor skills is not directly related to psychosocial development.

D. Incorrect. Administering a cognitive assessment focuses on intellectual abilities and may not provide a comprehensive view of social interactions.

Specimen collection

Explanation

A. Incorrect. While verifying medication with another nurse (a safety practice known as "the double-check") is important, it is not the highest priority action in this context.

B. Incorrect. Asking the child for their preferred method of administration may not always be feasible or appropriate, especially if the child is too young or uncooperative.

C. Correct. Before administering medication, it is crucial to verify the medication order against the patient's identification to ensure the right patient receives the right medication.

D. Incorrect. Administering the medication as prescribed by the provider is an important step, but first, it is essential to ensure the medication is intended for the correct patient.

Explanation

A. Correct. Mixing the medication with a preferred juice can help mask the taste and make it more palatable for the child.

B. Incorrect. While disguising the medication in food may be effective, it may not be suitable for all types of medications, and the nurse should consider the specific medication's administration requirements.

C. Incorrect. Holding the child's nose is not a recommended method for medication administration and may cause distress.

D. Incorrect. Administering medication intravenously is an invasive method and would only be appropriate if indicated for the specific medication and condition, not for general administration difficulties.

Explanation

A. Incorrect. Administering the medication with a rapid bolus may lead to inadequate delivery or potential aspiration.

B. Incorrect. Diluting the medication with water before administration should be done only if recommended by the provider or specified in the medication instructions.

C. Correct. When administering medication through a nasogastric tube, it is important to flush the tube with water before and after medication administration to ensure that the medication is properly delivered and does not remain in the tube.

D. Incorrect. Administering the medication without verifying the dosage is not a safe practice and could lead to medication errors.

Explanation

A. Correct. Many medications are formulated with a bitter taste to discourage accidental ingestion, especially in children who may be curious and prone to exploring their environment with their mouths.

B. Incorrect. While effectiveness is important, the bitter taste is primarily a safety feature.

C. Incorrect. While some medications may be combined to mask taste, the primary reason for bitterness is safety.

D. Incorrect. The taste can be significant, especially for children who may find bitter flavors unpleasant.

Explanation

A. Correct. Administering the medication with a dropper towards the back of the mouth helps ensure that the medication is swallowed rather than pushed out by the infant's tongue.

B. Incorrect. Mixing the medication with a bottle of formula may not guarantee that the full dose is ingested, as the infant may not finish the entire bottle.

C. Incorrect. Applying the medication to a pacifier may not provide precise dosing and may not be as effective as direct administration.

D. Incorrect. Using a spoon may be challenging for an infant and may not provide accurate dosing.

Explanation

A. Incorrect. Administering a double dose without provider approval can lead to overdose and potential harm to the child.

B. Correct. If a client is concerned about the medication dosage, it is crucial to advise them to verify the dosage with the prescribing provider to ensure accuracy and safety.

C. Incorrect. Skipping a dose without consulting the provider may lead to suboptimal treatment and may not be appropriate.

D. Incorrect. Crushing medication should only be done if it is safe and appropriate for the specific medication. It should not be a standard practice without provider guidance.

Explanation

A. Incorrect. Administering the medication with water alone may not effectively address the issue of the child's inability to chew the tablet.

B. Correct. If a child is unable to chew a tablet, crushing it and mixing it with a suitable substance (like applesauce) can help facilitate administration.

C. Incorrect. Discontinuing the medication without consulting the provider may not be appropriate and could lead to gaps in treatment.

D. Incorrect. While offering a different form of medication may be an option, it should be done under the guidance of the provider and may not always be necessary.

A client is administering ear drops to their 2-year-old child. How should the nurse instruct the client to administer the drops?

Explanation

A. Incorrect. Pulling the earlobe down and back is a technique used for administering ear drops in adults, not children.

B. Incorrect. Inserting the dropper deep into the ear canal is not recommended, as it can cause injury to the ear.

C. Correct. Having the child lie on their side with the affected ear facing up helps facilitate the proper administration of ear drops, ensuring that the drops reach the ear canal effectively.

D. Incorrect. Administering ear drops while the child is sitting upright may not allow the drops to reach the ear canal effectively.

Exams on Pediatric Nursing Skills and Pediatric Assessment

Custom Exams

Login to Create a Quiz

Click here to loginLessons

Nursingprepexams

Just Now

Nursingprepexams

Just Now

Notes Highlighting is available once you sign in. Login Here.

Objectives

- To provide a detailed overview of vital signs measurement in pediatric patients, including temperature, heart rate, respiratory rate, and blood pressure, emphasizing the nuances specific to children.

- To describe thorough headto-toe physical examination in pediatric patients, covering assessment of various body systems and developmental milestones.

- To highlight key milestones and characteristics at different stages of childhood, and challenges associated with each developmental phase.

- To outline best practices in pediatric medication administration, including dosage calculations, route selection, and age-appropriate communication, ensuring accurate and secure delivery of medications.

- To describe the common pediatric medications, including their applications, dosages, and crucial considerations for use, aiding in informed decision-making.

- To provide a comprehensive guide on specimen collection methods in pediatric patients, covering blood, urine, stool, and throat swabs, with an emphasis on age-appropriate and safe techniques.

Introduction

- Accurate measurement of vital signs is crucial in pediatric care.

- This guide provides a comprehensive overview of vital signs measurement, including temperature, heart rate, respiratory rate, and blood pressure.

- It also includes a detailed headto-toe physical examination.

It also covers developmental assessments across different stages of childhood, highlighting key milestones and characteristics.

- Understanding these aspects equips healthcare professionals with essential knowledge and skills for effective and tailored pediatric care.

- The guide outlines safe medication administration practices, including dosage calculations, route selection, and age-appropriate communication.

- It familiarizes readers with common pediatric medications, their applications, and important considerations for use.

- This comprehensive guide is a valuable resource for healthcare providers committed to delivering high-quality pediatric care.

Vital signs measurement

Temperature:

- Appropriate Sites for Measurement:

- Oral: Most common and suitable for cooperative children.

- Rectal: Most accurate but can be distressing for the child.

- Axillary: Least invasive but slightly less accurate.

- Tympanic: Quick and non-invasive, suitable for older children.

- Normal Pediatric Temperature Ranges Based on Age:

- Newborns: 97.7°F - 99.5°F (36.5°C - 37.5°C)

- Infants: 97.7°F - 99.5°F (36.5°C - 37.5°C)

- Toddlers/Preschoolers: 97.7°F - 99.5°F (36.5°C - 37.5°C)

- School-Age Children: 97.7°F - 99.5°F (36.5°C - 37.5°C)

- Adolescents: 97.0°F - 99.0°F (36.1°C - 37.2°C)

- Recognizing Signs of Fever and Hypothermia:

- Fever: Elevated body temperature, flushed skin, sweating, irritability.

- Hypothermia: Low body temperature, shivering, lethargy, pallor.

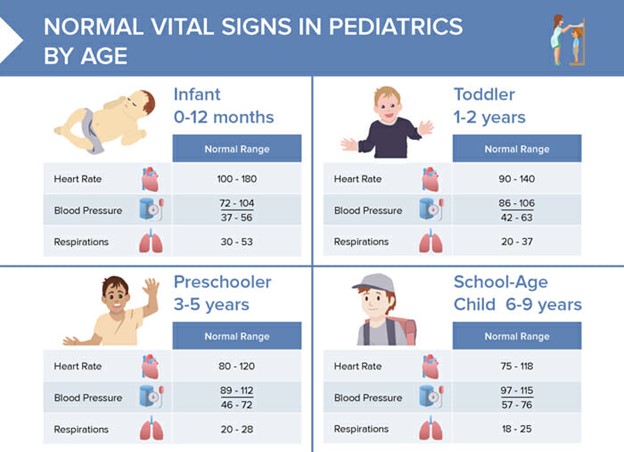

Heart Rate:

- Normal Pediatric Heart Rate Ranges Based on Age:

- Newborns: 120 - 160 bpm

- Infants (1-12 months): 80 - 140 bpm

- Toddlers (1-3 years): 80 - 130 bpm

- Preschoolers (3-6 years): 75 - 120 bpm

- School-Age Children (6-12 years): 70 - 110 bpm

- Adolescents (12-18 years): 60 - 100 bpm

- Assessing Heart Rate Rhythm and Regularity:

- Palpate pulse for strength, and regularity, note any irregularities (e.g., arrhythmias) and delays.

Respiratory Rate:

- Normal Pediatric Respiratory Rate Ranges Based on Age:

- Newborns: 30 - 60 breaths per minute

- Infants (1-12 months): 24 - 38 breaths per minute

- Toddlers (1-3 years): 22 - 34 breaths per minute

- Preschoolers (3-6 years): 20 - 30 breaths per minute

- School-Age Children (6-12 years): 18 - 26 breaths per minute

- Adolescents (12-18 years): 12 - 22 breaths per minute

- Assessing Respiratory Effort and Quality:

- Observe chest movement, use of accessory muscles,

- Signs of distress:

- Shortness of breath.

- Fast breathing, or taking lots of rapid, shallow breaths.

- Fast heart rate.

- Coughing produces phlegm.

- Blue fingernails or blue tone to the skin or lips.

- Extreme tiredness.

- Fever.

- Crackling sound in the lungs.

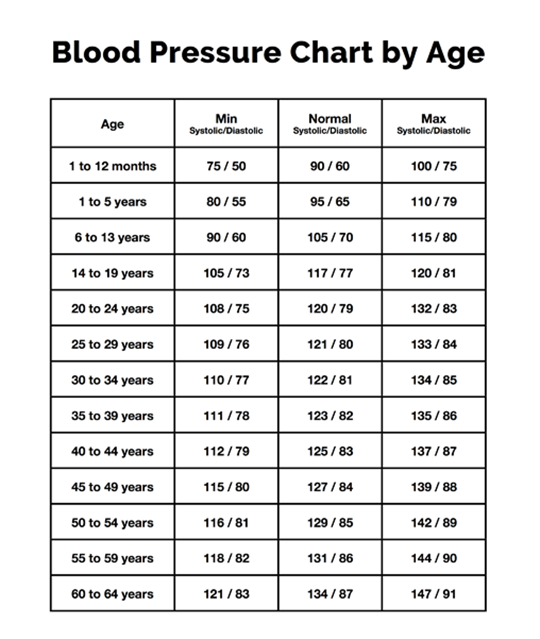

Blood Pressure:

- Determining Appropriate Cuff Size:

- Cuff width should cover 40% of the upper arm circumference.

- Normal Pediatric Blood Pressure Ranges Based on Age:

- Signs of Hypertension and Hypotension:

- Signs of Hypertension and Hypotension:

- Hypertension: Elevated blood pressure, headache, nosebleeds.

- Hypotension: Low blood pressure, dizziness, pallor, weakness.

Physical examination

- Performing a head-to-toe examination of a child is a systematic and comprehensive assessment to evaluate their overall health status.

- It involves observing and assessing various body systems from the head down to the toes.

- The head-to-toe examination in children involves:

1. Head and Face

- Inspection: Check for symmetry, shape, and size of the head. Note any abnormalities, lesions, or signs of trauma.

- Fontanelles: Assess fontanelles (soft spots) for size, tension, and flatness. Note any bulging or sunken fontanelles, which can be indicative of increased intracranial pressure.

- Eyes: Observe for symmetry, alignment, and presence of any discharge. Assess pupil size, shape, and reaction to light. Check for any signs of redness, swelling, or discharge.

- Ears: Inspect external ears for symmetry, position, and signs of abnormalities or discharge. Examine the ear canals for redness, swelling, or drainage.

- Nose: Check for any signs of congestion, discharge, or nasal flaring.

Mouth and Throat: Inspect the oral cavity for color, moisture, and lesions. Note any signs of tooth decay or gum issues. Assess the throat for any redness, swelling, or exudate.

2. Neck

- Inspection: Assess for symmetry, mobility, and any masses or abnormalities. Note any signs of enlarged lymph nodes.

- Palpation: Gently palpate the neck for tenderness, swelling, or enlarged lymph nodes. Check for range of motion.

3. Chest and Lungs

- Inspection: Observe for chest shape, respiratory rate, and use of accessory muscles. Note any retractions or signs of respiratory distress.

- Palpation: Check for tenderness, crepitus, or masses. Assess chest expansion and identify any areas of tenderness or abnormalities.

- Auscultation: Listen to breath sounds in various lung fields using a stethoscope. Note any wheezing, crackles, or diminished breath sounds.

4. Heart

- Auscultation: Listen to heart sounds using a stethoscope. Assess for rate, rhythm, and any abnormal heart sounds (murmurs, gallops).

5. Abdomen

- Inspection: Observe for shape, contour, and any visible abnormalities. Note any scars or distension.

- Palpation: Gently palpate the abdomen for tenderness, masses, and organ enlargement. Assess liver and spleen size.

- Auscultation: Listen for bowel sounds in all four quadrants.

6. Genitourinary

- Male Genitalia: Inspect for anomalies, hernias, and any signs of infection or inflammation.

- Female Genitalia: Inspect for anomalies, discharge, or signs of infection. In pre-pubertal children, avoid internal examination.

7. Musculoskeletal

- Inspect Extremities: Observe for symmetry, deformities, joint alignment, and muscle tone.

- Check Range of Motion: Assess the child's ability to move joints through their full range of motion. Note any limitations or discomfort.

- Palpate for Tenderness or Swelling: Examine joints and long bones for tenderness, swelling, or deformities.

8. Neurological

- Mental Status: Assess the level of consciousness, orientation, and mood.

- Cranial Nerves: Evaluate cranial nerve functions, including facial movements, pupillary responses, and gag reflex.

- Motor Function: Test muscle strength, tone, and coordination. Observe for any signs of weakness or abnormal movements.

- Sensory Function: Check sensation to touch, pain, and temperature in various areas of the body.

9. Skin

- General Inspection: Observe for color, temperature, moisture, and overall condition of the skin. Note any rashes, lesions, or bruising.

10. Back and Spine

- Inspection and Palpation: Check for symmetry, alignment, and any signs of abnormalities or tenderness. Note any curvature of the spine.

Developmental Assessment

Infancy (0-12 months)

Physical Development

- Birth weight doubles by 5-6 months, and triples by one year.

- Rapid growth in length, with an average of about 1 inch per month.

- Head circumference increases by about 1/2 inch per month.

Motor Development

- Lifts head and chest when lying on stomach (around 2-4 months).

- Rolls over from front to back and back to front (around 4-6 months).

- Sits without support (around 6-8 months).

- Crawls or starts to crawl (around 7-10 months).

- Pulls up to stand and may take a few steps (around 9-12 months).

Sensory and Cognitive Development

- Begins to focus on objects and faces, and tracks moving objects.

- Begins to explore objects by mouthing and touching.

- Responds to own name and familiar voices.

- Begins to imitate gestures and sounds.

- Develops separation anxiety around 6-8 months.

Social and Emotional Development

- Forms strong attachments to caregivers.

- Smiles and shows enjoyment during interactions.

- May display stranger anxiety.

- Begins to show signs of basic emotions like joy, anger, and distress.

Early Childhood (1-5 years)

Physical Development

- Slower but steady growth in height and weight.

- Fine motor skills develop, allowing for activities like drawing, building with blocks, and self-feeding.

Motor Development

- Walks, runs, climbs, and balances.

- Throws and catches a ball, kicks with some accuracy.

- Hops and skips.

- Starts to dress and undress with minimal assistance.

Cognitive Development

- Learns basic shapes, colors, and numbers.

- Begins to understand cause-and-effect relationships.

- Engages in imaginative play and storytelling.

- Expands vocabulary and starts forming sentences.

Social and Emotional Development

- Forms friendships and begins to understand sharing and cooperation.

- Develop a sense of self and personal preferences.

- Shows empathy and concern for others.

- Exhibits independence and may test limits.

Middle Childhood (6-12 years)

Physical Development

- Steady growth continues, with a more gradual pace than earlier years.

- Muscle strength and coordination improve, leading to better athletic abilities.

Cognitive Development

- Expands knowledge base, with improved reading, writing, and math skills.

- Begins to think logically and solve problems.

- Shows an interest in more complex concepts and subjects.

Social and Emotional Development

- Forms deeper friendships with peers and may have "best friends."

- Develops a sense of belonging within social groups or teams.

- Begins to understand and follow rules and expectations.

- Shows increasing independence and responsibility.

Adolescence (13-18 years)

Physical Development

- Undergoes rapid growth spurts, particularly during early adolescence.

- Experiences puberty, including physical changes related to sexual development.

Cognitive Development

- Gains more abstract thinking abilities, including critical thinking and long-term planning.

- Develops a more sophisticated understanding of complex concepts.

Social and Emotional Development

- Forms romantic relationships and explores personal identity.

- Seeks greater independence from parents and begins to make more independent decisions.

- Develop a sense of self-esteem and identity.

- Grapples with social pressures, peer influence, and self-image.

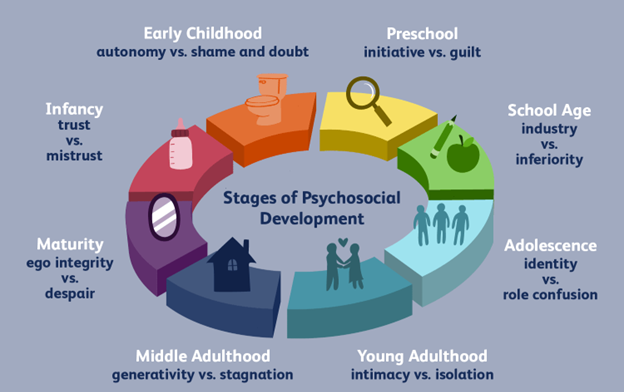

Erikson's Stages of Psychosocial Development

Erik Erikson was a renowned psychologist who proposed a theory of psychosocial development, outlining eight stages that individuals go through across their lifespan.

Each stage is characterized by a specific psychosocial conflict or challenges that a person must navigate in order to develop a healthy sense of self.

1. Trust vs. Mistrust (Infancy, 0-1 year)

- Conflict: The primary task is to develop a sense of trust in the world and in caregivers.

- Key Factors: Responsive and consistent caregiving helps the infant form a secure attachment, leading to a sense of trust. Inconsistent or neglectful care can lead to mistrust and insecurity.

2. Autonomy vs. Shame and Doubt (Early Childhood, 1-3 years)

- Conflict: The child begins to assert independence and autonomy. The challenge is to balance this newfound independence with boundaries set by caregivers.

- Key Factors: Encouragement of self-expression, exploration, and decision-making fosters a sense of autonomy. Overly controlling or harsh criticism can lead to feelings of shame and doubt.

3. Initiative vs. Guilt (Preschool, 3-6 years)

- Conflict: The child starts to take initiative in play and social interactions. They need to learn to balance their desires with consideration for others.

- Key Factors: Encouraging a child's curiosity, allowing them to explore, and providing opportunities for decision-making helps them develop a sense of purpose and initiative. Over-criticism or excessive control can lead to feelings of guilt and self-doubt.

4. Industry vs. Inferiority (School Age, 6-12 years)

- Conflict: Children begin to develop a sense of competence and mastery over skills and tasks. They need to feel valued and capable of achieving goals.

- Key Factors: Providing opportunities for success, recognizing achievements, and offering positive reinforcement helps build a sense of industry. Excessive criticism or unrealistic expectations can lead to feelings of inadequacy and inferiority.

5. Identity vs. Role Confusion (Adolescence, 12-18 years)

- Conflict: Adolescents are focused on forming a clear sense of self, including their values, beliefs, and aspirations. They navigate questions of identity and purpose.

- Key Factors: Encouraging exploration of personal values, interests, and roles, while providing support and guidance, helps foster a strong sense of identity. Lack of support or pressure to conform can lead to confusion and identity crisis.

6. Intimacy vs. Isolation (Young Adulthood, 18-40 years)

- Conflict: Young adults seek to establish meaningful, close relationships with others. This involves forming deep connections and the ability to commit to others.

- Key Factors: Developing trust and vulnerability in relationships, as well as maintaining a sense of individuality within partnerships, helps establish intimacy. Fear of rejection or excessive self-isolation can lead to feelings of loneliness and isolation.

7. Generativity vs. Stagnation (Middle Adulthood, 40-65 years)

- Conflict: Adults in this stage focus on contributing to society and future generations. They seek to leave a positive impact on the world and nurture the next generation.

- Key Factors: Finding meaningful ways to give back, mentor, and contribute to the community fosters a sense of generativity. A lack of purpose or involvement can lead to feelings of stagnation.

8. Ego Integrity vs. Despair (Late Adulthood, 65+ years)

- Conflict: Older adults reflect on their life and accomplishments. They seek to find a sense of fulfillment and acceptance of their life's journey.

- Key Factors: Coming to terms with life events, finding satisfaction in achievements, and accepting the inevitability of mortality leads to a sense of integrity. Regret and a lack of acceptance can lead to feelings of despair.

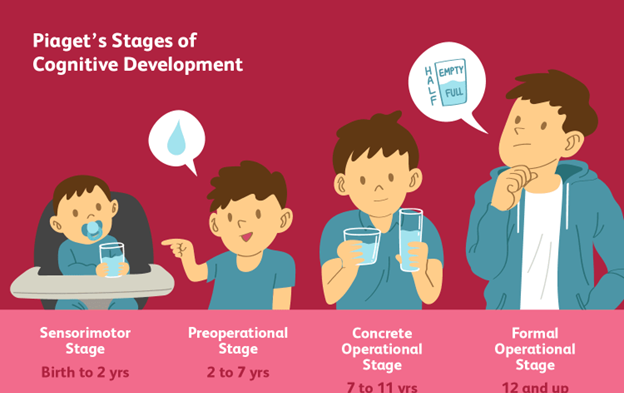

Piaget's Stages of Cognitive Development

Jean Piaget was a Swiss psychologist who made significant contributions to our understanding of how children develop cognitively. He proposed a theory of cognitive development that consists of four main stages, each characterized by distinct cognitive abilities and ways of thinking. Here are Piaget's stages of cognitive development:

1. Sensorimotor Stage (Birth to 2 years)

Key Characteristics

- Object Permanence: Understanding that objects continue to exist even when they are not directly perceived.

- Stranger Anxiety: Developing a sense of familiarity with primary caregivers and becoming cautious or anxious around strangers.

- Motor Skills Development: Progressing from reflexive, instinctual movements to purposeful, goal-directed actions.

Activities and Milestones

- Engaging in sensory exploration through touching, mouthing, and grasping objects.

- Developing basic problem-solving skills, such as using trial and error to achieve goals.

- Beginning to imitate simple actions and gestures.

2. Preoperational Stage (2 to 7 years)

Key Characteristics

- Egocentrism: Difficulty understanding and considering other people's perspectives.

- Centration: Focusing on one aspect of a situation and ignoring other relevant aspects.

- Symbolic Representation: Ability to mentally represent objects and events through symbols, such as language and imagination.

Activities and Milestones

- Engaging in imaginative play and make-believe.

- Developing language skills and the ability to ask questions.

- Demonstrating an increasing understanding of symbols and concepts.

3. Concrete Operational Stage (7 to 11 years)

Key Characteristics

- Conservation: Understanding that quantity remains the same even when the shape or arrangement changes.

- Reversibility: Grasping that actions can be undone or reversed.

- Logical Thinking: Gaining the ability to think logically about concrete objects and events.

Activities and Milestones

- Demonstrating an understanding of basic arithmetic operations (addition, subtraction, multiplication, division).

- Solving practical problems involving real-world objects and situations.

- Developing a grasp of cause-and-effect relationships.

4. Formal Operational Stage (11 years and beyond)

Key Characteristics

- Abstract Thinking: Ability to think abstractly and reason about hypothetical situations.

- Hypothetical-Deductive Reasoning: Ability to form hypotheses and systematically test them.

- Metacognition: Awareness and understanding of one's own thought processes.

Activities and Milestones

- Engaging in complex problem-solving and critical thinking.

- Developing the ability to think about and plan for the future.

- Demonstrating an increased capacity for understanding and engaging with complex concepts in various academic disciplines.

Psychosocial Assessment

1. Demographic Information

- Name, age, gender, ethnicity, living situation, and primary language spoken at home.

- Family composition and significant caregivers/guardians.

2. Presenting Concerns

- The reason for seeking assessment or intervention. This could include behavioral issues, academic struggles, emotional concerns, etc.

- Information on the duration and frequency of the concern.

3. Developmental History

- Milestones achieved in areas such as language, motor skills, social interactions, and cognitive abilities.

- Any history of developmental delays or milestones reached earlier or later than expected.

4. Medical History

- Any significant medical conditions, chronic illnesses, allergies, or recent illnesses/injuries.

- History of hospitalizations, surgeries, or ongoing treatments.

5. Educational History

- Grade level, school attendance, performance, and any special education services or accommodations received.

- Information on extracurricular activities, interests, and strengths.

6. Social History

- Information about the child's social environment, including family dynamics, relationships with siblings, peers, and significant adults.

- Any significant life changes or stressors (e.g., divorce, relocation, loss of a loved one).

7. Emotional and Behavioral Functioning

- Mood and affect: Assess the child's general mood, and expressions of happiness, sadness, anxiety, or anger.

- Behavioral observations: Note any behaviors that are age-appropriate or concerning (e.g., aggression, withdrawal).

- Sleep patterns and any sleep disturbances.

8. Family History and Dynamics

- Family structure, including information about parents/guardians, siblings, and extended family members.

- History of mental health issues, substance use, or other significant family stressors.

9. Safety and Risk Assessment

- Evaluate the child's safety and well-being at home, school, and in the community.

- Assess for any signs of abuse, neglect, or exposure to domestic violence.

10. Cultural Considerations

- Understanding the cultural background and values of the child and their family, which can influence their perceptions, beliefs, and behaviors.

11. Strengths and Resilience

- Identify the child's areas of strength, talents, and positive coping mechanisms.

- Acknowledge any support systems, hobbies, or activities that contribute to the child's well-being.

12. Parent/Guardian Input

- Obtain insights from parents/guardians about their perceptions of the child's behavior, emotions, and overall functioning.

- Inquire about any concerns or specific goals they have for their child.

Specimen collection

1. Blood Collection

Venipuncture

- Choose an appropriate site (often the antecubital fossa) and select the correct needle size based on the child's age and size.

- Apply a topical anesthetic or use a numbing cream to reduce pain.

- Ensure the child is calm and in a comfortable position.

- Use distraction techniques (e.g., toys, videos) to divert their attention.

- Have a comfort item or a favorite toy nearby for reassurance.

- Ensure a skilled and experienced phlebotomist performs the procedure.

Heel Stick (for infants)

- Clean the heel with an alcohol swab and allow it to dry.

- Warm the heel to increase blood flow (optional).

- Use a lancet to puncture the side of the heel.

- Collect the necessary amount of blood onto a filter paper or a microcollection tube.

- Apply gentle pressure to the puncture site to stop bleeding.

2. Urine Collection

Clean-Catch Method

- Clean the genital area thoroughly with wipes or soap and water.

- Provide a sterile urine collection cup.

- Instruct the child to start urinating into the toilet and then collect the midstream portion in the cup.

- Ensure proper labeling and timely transport of the specimen to the laboratory.

Bagged Urine Collection (for infants and toddlers)

- Apply a sterile adhesive bag over the genital area.

- Monitor the child for signs of urination.

- Once urine is collected, carefully remove the bag and transfer the urine to a sterile container.

3. Stool Collection

Clean Technique

- Provide a clean, dry bedpan or diaper liner.

- Instruct the caregiver to collect a small portion of the stool using a clean spoon or a designated collection device.

- Ensure proper labeling and transfer of the specimen to a sterile container.

4. Throat Swab (for bacterial cultures):

- Use a sterile swab to gently rub the tonsils and the back of the throat.

- Be careful to avoid causing discomfort or triggering a gag reflex.

- Ensure the swab reaches areas likely to harbor pathogens.

5. Nasopharyngeal Swab (for respiratory viruses)

- Insert a flexible swab through the nostril until it reaches the posterior nasopharynx.

- Gently rotate the swab to collect a sample.

- Ensure the swab does not touch the tongue or the palate.

Medication administration

i. Dosage Calculations for Pediatric Medications

1. Dosage Calculations Based on Weight

Step 1: Determine the Ordered Dose

Step 2: Check the Medication Label

Step 3: Convert Weight Units

Step 4: Calculate the Desired Dose

- Use the formula:

- Desired Dose (mg) = Ordered Dose (mg/kg) × Weight (kg)

Step 5: Administer the Correct Dose

2. Dosage Calculations Based on Body Surface Area (BSA)

Step 1: Determine the Ordered Dose

Step 2: Check the Medication Label:

Step 3: Calculate BSA

- Use a BSA calculator or the Mosteller formula:

- BSA (m²) = √[(Height (cm) × Weight (kg)) / 3600]

Step 4: Calculate the Desired Dose

- Use the formula:

- Desired Dose (mg) = Ordered Dose (mg/m²) × BSA (m²)

Step 5: Administer the Correct Dose

ii. Safe Medication Administration in Children

Safe administration of medication in children is of paramount importance to ensure their well-being and prevent potential harm. It requires careful attention to dosage, route of administration, and consideration of the child's age, weight, and individual characteristics.

1. Accurate Dosage Calculations

- Calculate medication dosages based on the child's weight or body surface area, following established pediatric dosing guidelines.

- Double-check all calculations with a colleague or by using a calculator to minimize errors.

2. Verify Medication Orders

- Confirm the medication order with the prescribing healthcare provider, especially if there are any discrepancies or uncertainties.

3. Check Medication Labels

- Ensure that the medication name, dose, concentration, and expiration date match the prescription. Be cautious with look-alike or sound-alike medications.

4. Use Age-Appropriate Formulations

- Administer medications in forms suitable for the child's age (e.g., liquid vs. tablet). Be cautious with crushing or cutting medications as some should not be altered.

5. Confirm Patient Identity

- Use at least two patient identifiers (e.g., name and date of birth) before administering any medication to verify the correct patient.

6. Administer at the Right Time

- Administer medications at the prescribed times to maintain therapeutic levels in the body.

7. Select the Correct Route

- Choose the appropriate route of administration (e.g., oral, intravenous, intramuscular) based on the medication and the child's condition.

8. Maintain Proper Technique

- Follow the aseptic technique during medication preparation and administration to prevent contamination and infection.

9. Provide Age-Appropriate Education

- Offer clear, age-appropriate explanations to the child (when developmentally appropriate) and caregivers about the medication, its purpose, and any potential side effects.

10. Use Developmentally Appropriate Communication

- Tailor your communication style to the child's age and cognitive level. For younger children, use simple language and incorporate play to ease anxiety.

11. Observe for Allergies and Adverse Reactions

- Prior to administration, confirm allergies and ask about any previous adverse reactions to the medication.

12. Monitor for Side Effects

- Continuously observe the child for any immediate side effects or adverse reactions after medication administration.

13. Document Thoroughly

- Record all pertinent information, including the medication name, dosage, route, date, time, and any observed effects or concerns.

14. Follow Up and Evaluation

- Monitor the child's response to the medication over time, and report any significant changes or concerns to the healthcare provider.

15. Store Medications Safely

- Keep medications out of the reach of children and in a secure, designated area to prevent accidental ingestion.

16. Adhere to Legal and Ethical Guidelines

- Follow institutional policies and legal regulations regarding medication administration and documentation.

iii. Common Pediatric Medications:

Common medications in pediatrics encompass a range of drugs used to treat various conditions in children. It's crucial to remember that dosages, formulations, and administration methods may vary based on a child's age, weight, and specific health needs. Here are some of the frequently prescribed medications in pediatrics, along with their common uses:

1. Analgesics and Antipyretics

- Acetaminophen (Tylenol): Used to reduce pain and fever in children. Available in various formulations, including liquid and chewable tablets.

- Ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin): Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) used for pain relief and to reduce fever. Suitable for children over a certain age and weight.

2. Antibiotics

- Amoxicillin: A broad-spectrum antibiotic used to treat bacterial infections such as ear infections, respiratory tract infections, and urinary tract infections.

- Azithromycin (Zithromax): Used for a wide range of bacterial infections, including respiratory and skin infections.

3. Respiratory Medications

- Albuterol (Proventil, Ventolin): A bronchodilator used to relieve asthma symptoms by opening airways.

- Inhaled Corticosteroids (e.g., Fluticasone - Flovent): Used as a maintenance treatment for asthma to reduce inflammation in the airways.

4. Antihistamines

- Diphenhydramine (Benadryl): Used to relieve allergy symptoms such as itching, sneezing, and runny nose. Can also be used as a sleep aid.

5. Gastrointestinal Medications

- Omeprazole (Prilosec): Proton pump inhibitor (PPI) used to treat gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) and stomach ulcers.

- Ondansetron (Zofran): Antiemetic used to prevent nausea and vomiting, often administered before surgery or chemotherapy.

6. Anticonvulsants

- Levetiracetam (Keppra): Used to control seizures in children with epilepsy.

- Lamotrigine (Lamictal): Another anticonvulsant used to treat epilepsy, particularly in older children and adolescents.

7. Steroids

- Prednisolone: A corticosteroid used to treat inflammatory conditions, such as asthma exacerbations and certain autoimmune disorders.

8. Vaccines

- Various vaccines are administered to prevent a range of infectious diseases, including measles, mumps, rubella, polio, diphtheria, pertussis, tetanus, influenza, and more.

9. Topical Medications

- Hydrocortisone Cream: Used to alleviate itching and inflammation associated with skin conditions like eczema and insect bites.

- Mupirocin (Bactroban): Topical antibiotic used to treat skin infections and prevent bacterial colonization in wounds.

10. Antifungals

- Nystatin (Mycostatin): Used to treat fungal infections like thrush in the mouth and diaper rash caused by yeast.

Summary

- Pediatric nursing focuses on holistic care for children, covering physical, developmental, psychosocial, and medical aspects.

- Child-centered care: It recognizes children as unique individuals with specific needs and developmental stages.

- Vital Signs: Proficiency in measuring and interpreting vital signs is crucial for assessing a child's health status and treatment response.

- Physical Examination: Pediatric nurses conduct systematic examinations, considering growth, neurological status, and musculoskeletal system, adapting techniques for different ages.

- Developmental Assessment: They monitor milestones in physical, cognitive, social, and emotional growth, identifying any delays or concerns.

- Psychosocial Assessment: Nurses evaluate a child's emotional and psychological well-being, providing support or referrals for any distress or behavioral issues.

- Specimen Collection: Pediatric nurses collect specimens with precision, ensuring safety and minimal discomfort for the child.

- Medication Administration: They administer medications accurately, considering dosage, age-appropriate formulations, and techniques to alleviate anxiety in the child.

Conclusion

- Pediatric nursing encompasses a holistic approach, addressing the physical, developmental, psychosocial, and medical needs of children. This comprehensive care ensures a thorough evaluation and timely intervention for optimal child development.

- Effective communication skills are fundamental in pediatric nursing. The ability to communicate with children and their families in an age-appropriate and empathetic manner establishes trust and comfort, forming the cornerstone of quality care.

- Proficiency in measuring vital signs, conducting physical examinations, and assessing developmental and psychosocial aspects empowers pediatric nurses to detect potential health issues early. This early intervention is pivotal in safeguarding a child's well-being.

- Collaboration with families is central to pediatric nursing. Involving parents and caregivers in the care process fosters a supportive environment and enhances overall outcomes for the child.

- Pediatric nurses are adept in specimen collection and medication administration, ensuring procedures are conducted with precision, safety, and minimal discomfort for the child.

- Proficient pediatric nursing skills not only contribute to the well-being of individual children but also play a vital role in shaping the future health of communities. By providing specialized care and support, pediatric nurses contribute significantly to the health and development of the next generation.

Nursingprepexams

Videos

Login to View Video

Click here to loginTake Notes on Pediatric Nursing Skills and Pediatric Assessment

This filled cannot be empty